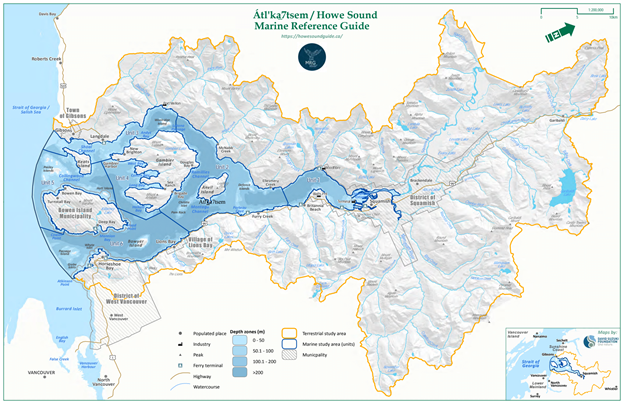

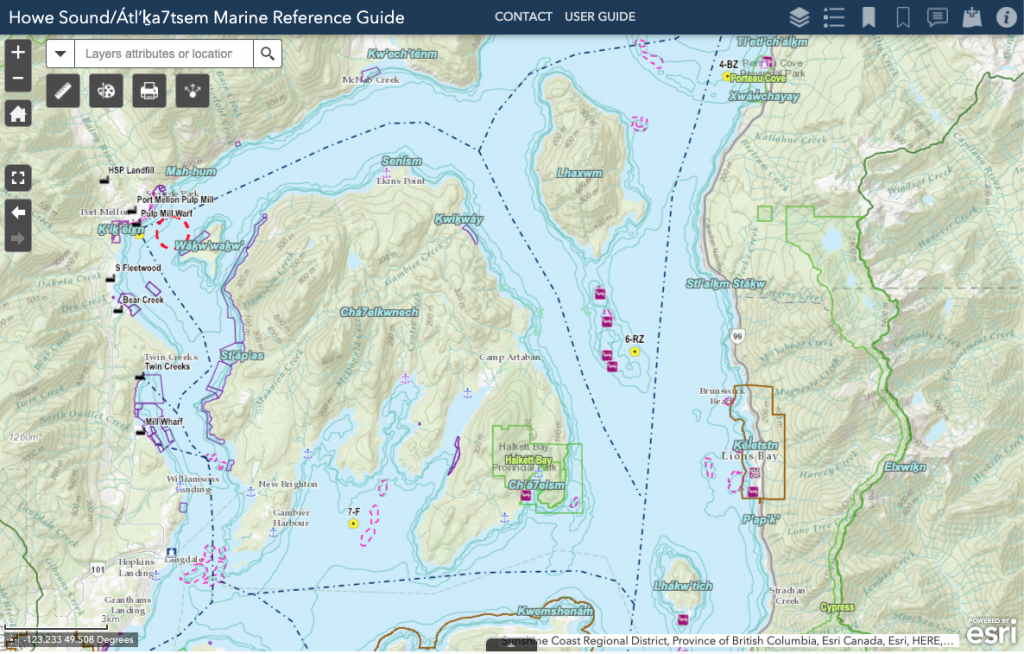

Nestled on British Columbia’s southern coast, the ecologically and culturally important region of Átl’ḵa7tsem (Howe Sound) has a new stewardship and planning tool in its pocket. On World Oceans Day, (June 8th), The Howe Sound/ Átl’ḵa7tsem Marine Reference Guide – a project on MakeWay’s shared platform – launched an interactive map with over 400 data layers to help stakeholders with future planning and development initiatives as the region grows in popularity, and its marine ecosystem and sacred cultural sites face additional pressures.

Átl’ḵa7tsem sits adjacent to the City of Vancouver and is home to diverse marine life, including glass sponge reefs, orcas, sea lions, and marine birds. The Sound lies within traditional Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) Nation territory, and overlaps and neighbours Tsleil-Waututh, xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), and shíshálh (Sechelt) Nations.

Industry threatens biodiversity through the 20th century

Throughout the 20th century, Átl’ḵa7tsem was developed primarily for industry. Halfway up the eastern shore of the Sound, the Britannia Beach Copper Mine was the largest of its kind in the British Empire, and one of the biggest sources of metal pollution in North America. The mine closed in 1974, but remediation efforts did not begin until 2001. In 2011, pink salmon returned to Britannia Creek for the first time in over a century.

Settlers established the town of Squamish at the northern edge of the Sound in the early 1900s as a hub for logging, and pulp and paper milling. These industries made significant ecological impacts on Átl’ḵa7tsem’s biosphere.

“I think the Guide’s greatest accomplishment is its collaboration, not only with elected officials and leaders, but also with the general community and with different organizations coming together to bring this initiative to fruition. I was really excited to see the community engagement that took place.” – Joyce Williams, Squamish Nation Councillor

Over the past several decades, the Átl’ḵa7tsem’s ocean health has improved due to the closure of mines and pulp mills, the implementation of better practices by currently operating industries, and the stewardship and restoration work championed by community members.

However, new threats to Átl’ḵa7tsem have presented themselves. Climate change is noticeable in the region, as nearby mountain glaciers melt and water temperatures rise. There is increased urbanization in the Sea to Sky corridor between Vancouver and the resort town of Whistler, including significantly increased tourism following the 2010 Olympics, and heightened interest in mountain activities including biking, rock climbing, and hiking. These factors have left people in the region wondering how to cope with new challenges to the ecological, cultural, and socio-economic health of the area.

The Howe Sound/Átl’ḵa7tsem Marine Reference Guide

With a goal to build capacity to protect, restore, and facilitate collaborative stewardship of Átl’ḵa7tsem, the Marine Reference Guide team (MRG team) began working on a three-year timeline in 2018.

Spurred by a 2017 Ocean Watch report on the health of Átl’ḵa7tsem, elected officials from the Sound’s local governments proposed the idea of bringing together as many of the region’s stakeholders as possible to create a comprehensive, interactive map of the Howe Sound marine area, in order to facilitate regional planning and decision making going forward. Fiona Beaty, the project’s director, also wanted to create a resource that could help the local community increase their knowledge about Howe Sound.

The MRG team is made up of eleven researchers and dedicated volunteers. It has a steering committee of 12 members including municipal leadership, Squamish Nation, local business owners, federal stakeholders, and environmental organizations. Three Squamish Nation youth, Myia Antone, Jonny Williams, and Nolan Rudkowsky, led the youth engagement element of the project, working with communities around Átl’ḵa7tsem to create strategies for elevating Indigenous youth voices and participation in marine stewardship.

With four First Nations, nine local governments, and several other stakeholders in the area, there were already several maps of various parts of the Sound, but no one single resource covering the whole of the Sound. “But fish swim across administrative barriers,” said Fiona, “and so we wanted to create a comprehensive resource, bringing together all of the existing data sets, and identifying and filling the gaps, to centralize our knowledge of the region.”

The first step of a long-term action plan to protect Átl’ḵa7tsem’s ecological integrity, the Marine Reference Guide “braids together multiple ways of knowing.” Utilizing natural sciences to map the area, the team also conducted lengthy qualitative research, interviewing knowledge holders in the region, to understand its historical, current, and future significance to communities both First Nation and settler. The Guide is the first tool to involve multisectoral leadership in bringing together knowledge associated with Átl’ḵa7tsem’s marine ecological and human-use values.

“The Marine Reference Guide is a fantastic example of bringing knowledge together from multiple sources,” said Islands Trustee Kate-Louise Stamford. “Governments and traditional knowledge keepers each hold valuable information about this complex area, but it isn’t until it all comes together that you really see how truly amazing and diverse Átl’ḵa7tsem is. And that’s what the Marine Reference Guide does.”

In addition, the team have mapped out a community network of everyone in the region whose work intersects in Átl’ḵa7tsem, in order to convene a more close-knit community of like-minded folks. “Like a visual directory,” said Fiona, “to show who is doing what, and where.”

Together, these two resources will support decision makers so that regional environmental health and sustainable economic and community development can flourish in tandem moving forward, building capacity and setting a precedent for regional co-management.

One of the challenges the team encountered was in synthesizing so much data from diverse stakeholders: “creating consensus-building processes necessitates compromise,” said Fiona, which can prove difficult when bringing together so many passionate individuals and community groups.

Working through that led to an unexpected reward: the process bolstered the energy of Squamish Nation youth, who were inspired to deepen their connection to their Territory. The Guide has “come to life through the leadership of young people in the Sound,” said the team, because of their commitment to strengthening their community’s connection to place and filling in knowledge gaps by spearheading field research on plankton, herring, and eelgrass.

For example, Squamish Nation youth sought to understand the role of herring in their Territory. They learned survey techniques from citizen scientists who have documented these forage fish for decades, and ultimately transformed the research by bringing in elements of Squamish culture and language. The herring data then became one of the hundreds of layers of data incorporated into the Guide.

Finding a home on MakeWay’s Shared Platform

From the early days of the project, the team felt strongly about the need to bring a balanced approach. With a goal of creating consensus around a practical tool intended for use by various and numerous stakeholders, the team believed that creating a neutral structure to carry out the work was essential to the success of the project. MakeWay’s shared platform offered the best chance at fulfilling this.

“The shared platform provided everything we were hoping for when we signed on,” said Fiona. “Being part of MakeWay allowed us to focus on the work we need to do on the ground and in the community, and not worry about the administrative, budgeting, or fiduciary responsibilities, which I don’t have experience in.” Instead of getting bogged down in back-end tasks, the MakeWay shared platform model empowered the team to focus on fundraising, researching, convening, and creating the Guide.

Now that the Guide has launched, the initiative will begin the process of transferring the maintenance of the regional and community network maps over to the Howe Sound Biosphere Region Initiative. They are leading a campaign to have Howe Sound formally designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Region, which will mean it is formally recognized as having global ecological significance.