By Julie Price, Program Lead, Northern Manitoba

In my role as Program Lead, Northern Manitoba, I work with a large group of northern community members, advisors, funders, and organizations in the Northern Manitoba Food, Culture, and Community Collaborative (NMFCCC). The Collaborative supports communities in increasing access to healthy food, and improving community health and economic development.

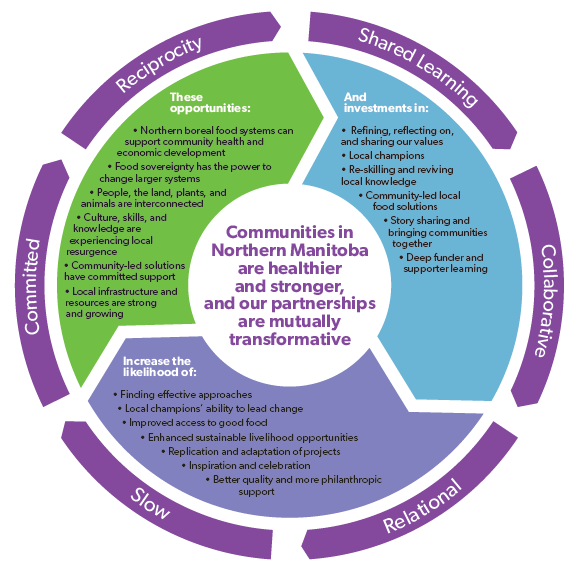

The NMFCCC began as a pilot in 2013 and became a fully-realized collaborative in 2014. An essential part of our journey as a Collaborative was documenting our methodology in a Theory of Change and describing our collective efforts and the community-led vision for change.

Developing the Theory of Change was a nearly four-year process of conference calls, emails, in-person meetings, and learning trips involving the Evaluation Committee, Northern Advisors, and at times, all Collaborative members. The process we used to create the Theory of Change was important because it reflected our group values and a way of working that the Collaborative’s Northern Advisors have shared. The Collaborative worked slowly and ensured all voices were heard, we worked relationally and in the spirit of reciprocity, and with the intent of learning from and with each other.

During our annual Learning Trip in September 2016 to the territory of Opaskwayak Cree Nation, the Evaluation Committee led us on the first deep, in-person discussion about the draft Theory of Change. The conversation happened early in the trip and the reverberations and follow-up discussions threaded throughout the rest of the trip.

Below are the key lessons and reflections we took away from the process of developing the Collaborative’s Theory of Change. These and stories from each community are also shared in the Collaborative’s latest publication 2017 Community Stories booklet.

-

- Start with your values: The Collaborative’s values were an excellent starting point given there was consensus on their general tone and scope. The values aptly described how we had been working so far and how we were being taught to develop relationships and build partnerships. It was necessary to ground our Theory in our values and ensure they were well reflected throughout.

- Concentrate on your primary goal: The Collaborative’s dual outcomes of bringing about community wellness via food security and related community economic development and of impacting philanthropic practice and knowledge were not readily agreed upon. In fact, the latter seemed jarring to many around the circle. Questions arose such as, “Since when did funders include their organizational or personal-level change/transformation in their granting work to communities? What did it mean to ‘decolonize philanthropy?’ Was this what I signed up for? Are we lacking humility to think that we could actually achieve such a goal as decolonizing philanthropy?” Happily, the goal of supporting community change via food projects was an easy agreement. Much more conversation was required before we could on consensus, understand, support, and describe our own change in terms of philanthropic practice and awareness.

- Focus on the positive: The typical approach to creating a theory of change is to focus on the problems we wanted to fix. The Indigenous people in the room (and on subsequent conference calls and meetings) gently explained that the time for a problems-focused approach had passed. People are aware of the problems and want to focus on the opportunities, solutions, resources, and people ready to make change. As a group, we needed to shift our hearts and language to a strengths-based approach.

- Make it inclusive and accessible: The initial draft Theory of Change was not something that community members felt proud of or saw themselves in. The language was academic and paternalistic. People did not want to be the subject of a Theory of Change or ‘do gooder’ actions, but rather they desired to be recognized as strong partners and visionary leaders of positive change. The Collaborative sought to transform the traditional “top-down” model of philanthropy by involving community and operate with values of reciprocity and collaboration. The Theory of Change also needed to reflect that.

- Be open and prepared to unlearn: A linear Theory of Change, as it was initially drafted, did not jive with an Indigenous worldview that emphasizes holistic understanding and interconnectedness. We needed to retrain our brains to think cyclically. We needed a Theory of Change that embraced a circular model or vision.

- Start with your values: The Collaborative’s values were an excellent starting point given there was consensus on their general tone and scope. The values aptly described how we had been working so far and how we were being taught to develop relationships and build partnerships. It was necessary to ground our Theory in our values and ensure they were well reflected throughout.

This process was important for the Collaborative as we unlearned and developed a new understanding and common agreement about our work. The TOC was finalized in spring of 2017 and has become a touchstone for our work. It is regularly referenced by funders, Northern Advisors, and staff in all aspects of our work including our grantmaking, reporting, and evaluation.

The NMFCCC welcomes and appreciates all feedback and questions about our Theory of Change. We see it as a living document that will change based on our evolving understanding and community needs.

The 2017 NMFCCC Community Stories booklet is now available. Learn more about NMFCCC and Tides Canada’s work with Collaboratives.