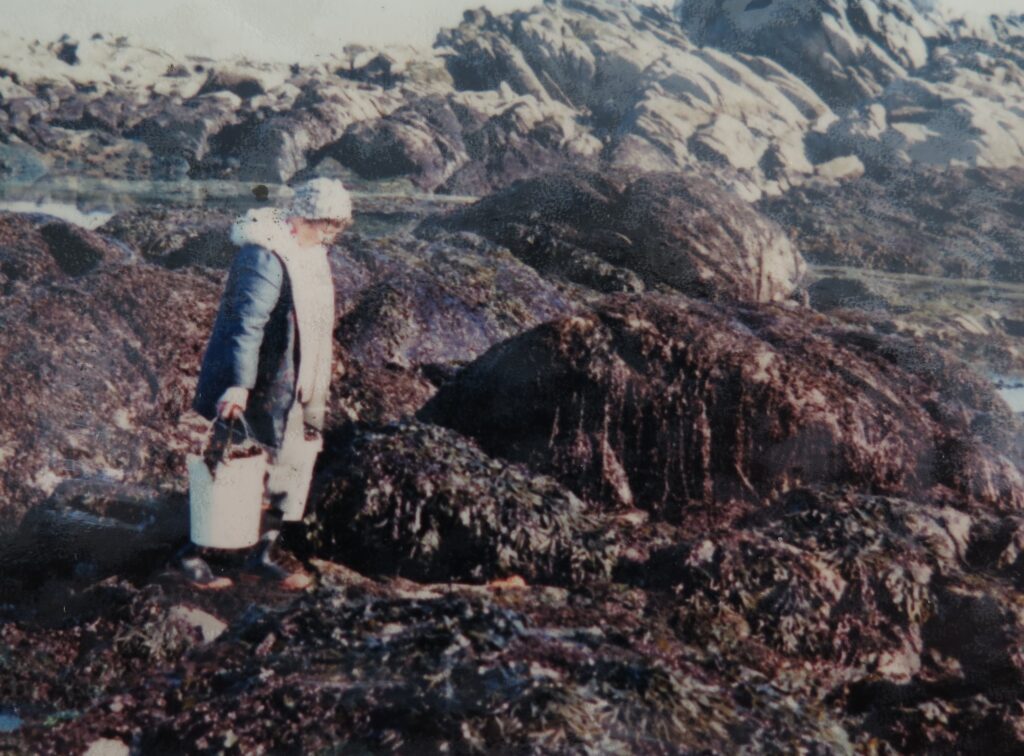

Braden Etzerza gained his appreciation for harvesting and sharing traditional foods through the Matriarch of his family on his Ts’msyen side. “My great grandmother had so much knowledge related to seafood harvesting and processing,” Braden remembers. “She was a master of her trade and craft and knew how to smoke sockeye salmon, jarr abalone, dry seaweed and halibut, or how to prepare chiton. She knew the importance of a healthy ecosystem and the benefits of eating our traditional foods. She always served us something amazing, whether it was laan [salmon eggs] and boiled laask [seaweed] with kwatsi [oolichan grease] or her famous curried tsaax [clams], she always prepared her food with love and knowledge passed down from our Ancestors.”

Photo: Braden Etzerza

Braden is now bringing that love of his homeland foods that he learned through generational knowledge transfers from his great grandmother to his work with MakeWay’s BC Program. His role is to build authentic kinships and find ways in which MakeWay can learn from communities and work in collaboration towards a range of holistic initiatives, including on Indigenous food systems, food sovereignty, and food security. “Indigenous food systems are brilliant and have existed since time immemorial,” he explains. “Indigenous food sovereignty is the ability to be in charge of one’s own food system and to be able to hunt, trap, fish, gather, and grow based on one’s own culture and ways of being.”

MakeWay has been supporting healthy and resilient food systems for the past 20 years, ranging from projects that protect wild salmon habitats, to marine planning, to Indigenous guardian initiatives. But the COVID-19 pandemic deepened our focus on food sovereignty and activated new relationships with Indigenous Nations, school districts, and community-based organizations. “When the pandemic first started, things were chaotic,” says Bridgitte Taylor, BC Program Team Lead at MakeWay. “Food security was an immediate need for many of our partners, particularly those living in more rural or ‘remote’ areas. In many of the communities, entire supply chains were cut off. The delivery of food, groceries, and emergency supplies were massively disrupted.”

“The pandemic exacerbated crises that have been present in many communities since first contact,” agrees Braden. “Many Nations have been dealing with suicide, overdose, and housing crises, as well as rapid industrial development and destruction of cultural and food harvesting sites. This has led to many Nations taking the lead on various food or related projects in their communities.” Projects like culture and language centres, community gardens, and land harvesting programs provide spaces where Elders can pass homeland knowledge and teachings to the next generations and are key to developing healthy, just, and secure food systems. “This work is a powerful form of healing from trauma and colonial impacts,” explains Braden. “It provides opportunities to connect with family, community, friends, and loved ones while communally harvesting food in the same places our Ancestors did.”

However, throughout the pandemic we heard from community partners that there was a lack of support for these projects, and the funding that was available was difficult to access or required communities to spend hours filling out laborious forms and wading through complex requirements. “Traditional philanthropy tends to reinforce power dynamics and inequities that hold transformative work back,” says Bridgitte. “The technical and bureaucratic hoops that communities often have to jump through to secure even modest funding is time taken away from advancing work on the ground.”

On top of that, many funding programs are siloed into specific issue areas or priorities. This rigidity isn’t always conducive to long-term outcomes and often does not align with holistic ways of working that are central to Indigenous-led work and ways of knowing. “If we’re able to support a community with their food work, how might we also partner to support their wider stewardship, or cultural resurgence goals? It’s all interconnected and can’t be tackled in isolation,” explains Bridgitte.

These are some of the reasons why less than 1% of philanthropic dollars in Canada support Indigenous-led work.

MakeWay is trying to change this. Last year, nearly 90% of MakeWay’s BC Program funding went directly to First Nations or Indigenous-led work. “Our approach to funding and relationships matter”, says Bridgitte. This approach was central to MakeWay’s COVID-19 emergency fund created in the early days of the pandemic. We also try not to reinforce the requirement of the written word, which is often at odds with Indigenous storytelling practices and oral histories, and we recognize that it takes time and intention to create long lasting relationships built on trust. “We provide support to communities through grantmaking, mentorship, and providing opportunities to meet in person,” adds Braden. “We meet communities where they are at – not always expecting them to come to us but actively reaching out to them through relationships, networks, and connections.”

Photo: Nak’al Bun Elementary.

Over the past year, MakeWay has been able to provide funding support to projects such as the Haida Gwaii museum, halibut hook, berry propagation, and spruce root basketry; a food forest based on an ancient perennial plant management system in Kitselas First Nation; and the Nawalakw Culture Project, a healing lodge located on the Hada River estuary that provides cultural programing and language revitalization camps for current and future generations.

MakeWay has committed to an initial three years of funding for food related work in BC: transformed and Indigenous food systems is a priority in our organization-wide strategy. This is just the beginning of our commitment to this work.

For Braden, Indigenous food systems represent a future full of possibility: “I see nations in BC thriving, healthy, and connected. I see food systems projects being recognized not only for their ability to provide healthy, local food, but also for their potential to re-localize food systems, their resilience to the effects of a changing climate, and their ability to provide culturally relevant and sustainable jobs for Indigenous people and community members. I see more opportunities for youth to become involved in Indigenous food projects. I see funders stepping up, streamlining, reducing barriers, and decolonizing their processes to better support Indigenous Nations, communities, and individuals in BC.”

“The future is in our hands and the next seven generations depend on us. It is our duty to caretake and do what we can to make the future a more equitable and just place for all, and to honor the original stewards of these lands.”