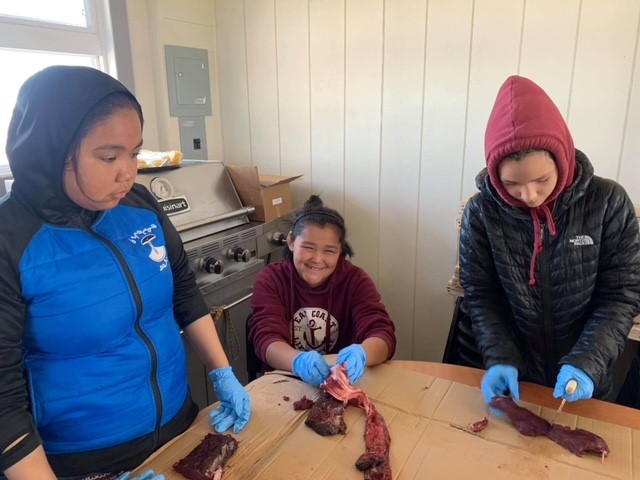

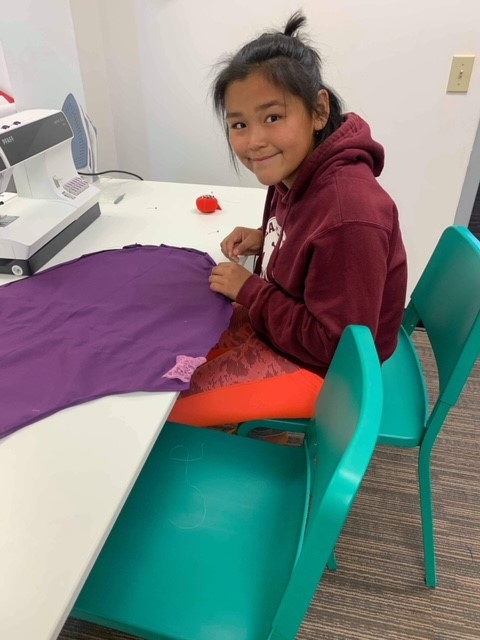

An innovative new program aims to bring opportunities and support to girls in the North. The Akpaliapik pilot program will offer organized activities for young girls and teens that are focused on developing well-being and identity through connection and pride in their culture, language, and heritage. It will offer a safe space to hang-out, learn, and grow surrounded by people and supports that will help them thrive.

“This cultural connection is key to strengthening their confidence and belief in themselves,” says Adriana Kusugak, executive director at Ilitaqsiniq (Nunavut Literacy Council), who is heading the program. “By helping girls and teens to feel connected to and proud of who they are, where they come from, what they can do, what their ancestors have done, we can show them their worthiness and how they have to keep striving and moving forward.”

With financial support from the Canadian Women’s Foundation in partnership with MakeWay and the support of the Grey Birch Foundation, the Akpaliapik program will serve two cohorts of 12-15 participants over 10 weeks, with one cohort made up of girls aged 9-13, and the other serving teen girls aged 13-16.

Kusugak has no doubts that the program will be well-received. “The girls are going to be happy to have somewhere to go, but there will be lots of hands-on activities around personal wellness, group building, as well as reflection time – all the things in our busy lives we don’t always necessarily take the time to do. But, if we teach this to the girls while they’re young, it might become part of their practice, and help them to have a healthier life balance in the future.” Program delivery will be supported by community elders and counsellors.

For young girls and teen girls in Rankin Inlet, there aren’t many places that you can go to simply hang out or be a part of activities that aren’t sports-based. There also isn’t much support for these girls whose lives are often touched by trauma, poverty, and violence.

Mentorship is a key component of the Akpaliapik program. The plan is to have grade 12 girls acting as co-facilitators. “We know that participants will relate more to girls that they see regularly, and by having grade 12 girls be a part of the program it’s helping to have that connection and know that there is someone they can turn to for help in a rough situation at school,” says Kelly Lindell, Kivalliq Program Manager for Ilitaqsiniq (Nunavut Literacy Council), who will be coordinating the sessions. This also helps build the capacity and skills of those grade 12 girls, with the hope that they might be able to develop, organize, and plan similar programs in the future.

“Those older girls are going to be able to have that relatable moment where they can say, “Yeah, when I was 13 this was hard for me, too,” or “this is how I got through this” or “this is who I use as a support,” Kusugak explains. “We want to show them that these girls in grade 12 are looking at pursuing postsecondary opportunities. They are role models within our community. They’re trying their best to live healthy lifestyles and make good choices for themselves. And I think that the younger ones need to know that. You know, even though you might make mistakes along the way or get derailed a little bit, you can still bring it back.”

Forging new partnerships in the North

The Canadian Women’s Foundation has long had an interest in funding northern projects but has historically found it difficult to connect with projects and organizations there. Partnering with MakeWay helped bridge that gap. “We have done grantmaking in the North, but we always felt like we were not really getting to all kinds of organizations,” explains Anuradha Dugal, Senior Director, Community Initiatives and Policy at the Canadian Women’s Foundation. “We wanted to make sure we were more receptive to the differences in the North and get in touch with what different groups were doing. Working with MakeWay enabled us to do that.”

To reach more women and girls in the North, the Canadian Women’s Foundation decided to build a specific northern strategy and hire someone who could help execute that. “We were not getting to the impact we wanted, which was hearing directly from organizations in the North about exactly what they wanted. Then we partnered with MakeWay to create a position where we could have somebody on the ground telling us what people needed,” Dugal says.

MakeWay senior associate Delma Autut was hired to fulfil that role (funded jointly by the Foundation and MakeWay) and acts as a bridge between projects in the North and the Canadian Women’s Foundation. Autut brings many years of experience and existing connections with those who run projects in the North, providing a vital link that outside organizations often struggle to make.

“A lot of the work that we do here is based on the relationships that you have with the organizations, and how well you understand their needs. Without having someone based in the North it was hard for the Canadian Women’s Foundation, and other organizations who are based in Southern Canada to come up here to try and do some work,” Autut explains. “Plus, MakeWay already has a ten-year relationship in the North, and I’ve had conversations with other organizations who absolutely love how MakeWay operates – we are a very flexible organization in terms of applications, proposal writing, being accessible and accommodating, and understanding.”

Dugal says that the Canadian Women’s Foundation has learned a lot about how projects operate in the North, including why their tried and tested application process created barriers for Northern projects. “For example, a lot of the ways that we have expected people to be able to do their grant proposals is through an online portal. I mean, we’ve always said you can just do it on an email and send it in. But even that means that people have to take the extra step to call us and say we need your word document, and then they have to download it,” Dugal says, “It’s lots of steps for organizations who are already tremendously busy and may not even believe that we would be open to that. So, having Delma there means that she can directly connect, she hears what they need. And then she says, “Okay, well, I’ll make that happen.”

Making it happen means breaking away from the traditional western and often-colonial requirements that are often put on projects seeking funding. “We help with proposal writing and are open to answering any questions around reviewing the proposals. We don’t have deadlines for the grants. We don’t have this crazy long list of criteria or boxes that we have to check, and where we do have requirements it is very flexible, making it easier for organizations with their programs,” Autut says.

In the many years that Autut has worked in the North, she has seen many organizations try to bring in projects and fail. “They don’t understand how it works here. You need to Nunavutize it! You need relationships with someone in the North so that you can grow, that partnership piece and connection to the North is really big!”

Akpaliapik is one of two projects currently being funded through the Canadian Women’s Foundation/MakeWay partnership, while more are set to follow. “This is exciting for us, and it’s just so nice to be in a place where we finally seem to have hit the right mechanisms, to make it happen in the way we were always hoping it would,” says Dugal.

Destined to succeed

Kusugak and Lindell are excited to get Akpaliapik up and running and are confident that it will be successful. “I already know that as soon as we put the advertisement out for the program we’re going to have so many more applicants than what we have room for,” says Kusugak. “Then they’re gonna be upset when it’s done, and say, “Awww, it’s already over, when are you going to do it again?” adds Lindell. They are hopeful that after the pilot program runs this will be something that they can continue in Rankin Inlet, and take to other communities.

“Ideally, it would be nice to have this going throughout the year, or a drop-in basis so that we can offer continual support to more girls,” says Lindell, “Often, youth here are left feeling “and now what?” so being more consistent with this programming would be incredibly helpful.” With the Foundation increasing access to funding for projects in the North, there’s a sense of optimism around what could be achieved. “We weren’t even aware of the opportunity that the Canadian Women’s Foundation made available to the different groups until MakeWay connected us, and it has given us a lot of confidence to know that a funder really is interested in the North, especially in the arctic and Nunavut, and in helping women and girls,” says Kusugak.